TPOCo Resources: Division of Labour – The Evolution of Human Cooperation

Introduction to Division of Labour

The division of labour ↗ has deep biological roots, beginning with the earliest form of cooperation: sexual reproduction ↗. As life evolved, this division extended to the cellular level ↗, where the human body now exemplifies this principle with its billions of cells, each specializing in roles that contribute to the whole organism’s survival. From muscle cells to neurons, these “specialist cells” work in harmony, showing that the division of labor is a natural and efficient way to manage energy within complex systems.

In early human societies, cooperation involved the physical sharing of tasks like hunting and gathering. This primitive division of labor was directly tied to the need for energy and survival. With the rise of agriculture and trade, labor became more specialized, leading to the development of distinct roles such as farmers, artisans, and traders. Money then emerged as the interface for sharing ↗, allowing for more complex exchanges and obscuring the direct link between cooperation and energy sharing.

Today, the division of labor has fragmented further ↗ into highly specialized fields of knowledge, creating an intricate and interdependent system of human cooperation. The sheer volume of knowledge produced daily is staggering; not a single human can absorb all the articles of Wikipedia, let alone the constant stream of news, scientific discoveries, and information shared through countless mediums. This increasing specialization requires a heightened level of coordination to align efforts, ensure effective collaboration, and maintain the system’s overall functionality. While money facilitates these exchanges, it often conceals the fundamental energy transactions that underpin cooperation.

Exploring the evolution of labor division reveals how deeply interconnected human cooperation is and how it forms the backbone of the TPOCo framework, continuously shaped by the ongoing need for coordination as labor becomes increasingly specialized.

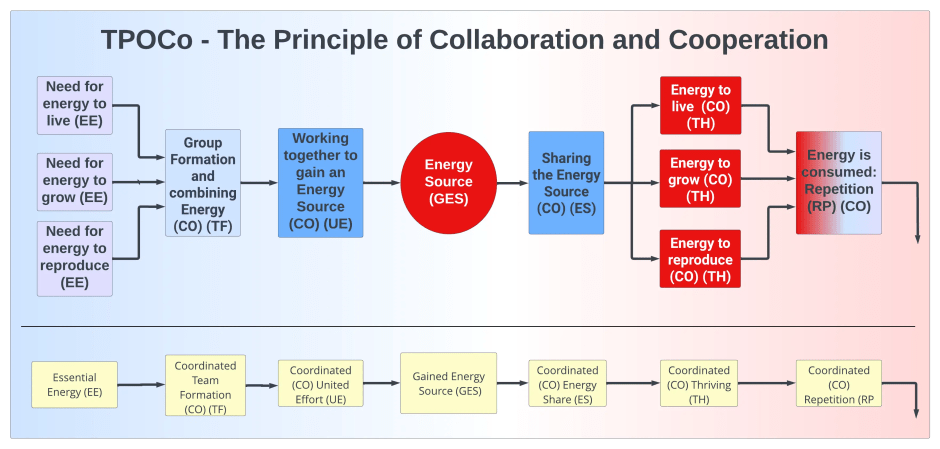

TPOCo Infographic – Detailing the journey from individual energy needs to collective thriving.

Book: “Life Ascending: The Ten Great Inventions of Evolution” by Nick Lane (Amazon ↗)

In “Life Ascending,” Nick Lane takes readers through ten key evolutionary breakthroughs that shaped life as we know it. Among these revolutionary “inventions” is the emergence of multicellular life and the development of cellular specialization. Lane illustrates how cells evolved to perform specific tasks, forming a complex division of labor within organisms. This specialization enabled the creation of intricate biological systems, optimizing energy use and supporting the organism’s survival and growth.

Lane’s exploration of cellular specialization provides a foundation for understanding the natural origins of the division of labor. Just as cells in a multicellular organism take on specialized roles—whether as muscle cells, neurons, or immune cells—human societies have evolved to include specialists in various fields. The efficiency gained from this division allows both natural and human systems to channel energy effectively and thrive.

“Life Ascending” gives readers an insight into how the division of labor is not just a human construct but a natural evolutionary strategy. By tracing these processes back to their biological roots, Lane’s work helps us understand the deep connections between the division of labor in nature and the sophisticated cooperative structures found in human society, as described in TPOCo.

Book: “The Lives of a Cell: Notes of a Biology Watcher” by Lewis Thomas (Amazon ↗)

In “The Lives of a Cell,” Lewis Thomas offers a series of reflections on the natural world, focusing on the interconnectedness of life and the division of labor within biological systems. He masterfully illustrates how the human body, with its billions of specialized cells, functions as a complex cooperative system. Each cell, whether it be a neuron, muscle cell, or immune cell, plays a distinct role in maintaining the organism’s health and vitality.

Thomas delves into how cells collaborate seamlessly, showcasing nature’s own division of labor. This cellular specialization mirrors the cooperation seen in human societies, where individuals take on specialized roles to serve the collective good. Thomas argues that the efficient functioning of life depends on this division, as it optimizes energy use and supports the organism’s ability to thrive.

“The Lives of a Cell” beautifully aligns with the TPOCo principles, illustrating that the division of labor is not unique to human society but a fundamental aspect of nature. It offers a lens through which we can understand how cooperation emerges from the intricate web of specialized roles, both within the human body and in broader human systems. By looking at life on a cellular level, Thomas provides a profound metaphor for human cooperation, emphasizing the importance of each individual’s contribution to the whole.

Book: “The Superorganism: The Beauty, Elegance, and Strangeness of Insect Societies” by Bert Hölldobler and E.O. Wilson (Amazon ↗)

In “The Superorganism,” Bert Hölldobler and E.O. Wilson take readers into the intricate world of insect societies, highlighting how cooperation and division of labor thrive outside of single organisms. Through a detailed examination of ants, bees, termites, and other social insects, the authors showcase how these creatures form highly organized societies where individuals perform specialized roles—workers, soldiers, queens—much like the organs and cells in a single organism.

Hölldobler and Wilson introduce the concept of the “superorganism,” where the collective society operates as a single entity through the cooperation and specialization of its members. This division of labor is the key to their survival and success, enabling the efficient gathering, distribution, and utilization of resources. The book reveals how these insect societies optimize energy use and adapt to changing environments, mirroring the processes seen in human cooperation.

“The Superorganism” offers a profound look at how nature has evolved complex systems of cooperation through the division of labor. It underscores that such cooperation is not just a human phenomenon but a universal strategy for survival and thriving. By examining insect societies, readers gain insight into how division of labor creates a cohesive system that maximizes the collective’s benefits, a principle that directly aligns with the TPOCo framework.